Search and Find

Service

More of the content

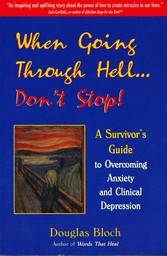

When Going Through Hell...Dont' Stop! - A Survivor's Guide to Overcoming Anxiety and Clinical Depression

“The journey to higher awareness is not a direct flight.

Challenges, struggles and tests confront the traveler along the way. Eventually, no matter who

you are or how far you have come along the path, you must experience your

‘dark night of the soul.’ ”

Douglas Bloch, Words That Heal

The notebook by the side of my bed was finally being put to use. Given to me by a friend so that I could record my dreams, the lined yellow paper had remained untouched for months, as my sleeping medication made dream recollection all but impossible.

“Oh, well, ” I mused. “It won’t matter much after today.”

I looked out the window. It was another of those oppressive Oregon winter skies that moves in like an unwanted house guest at the beginning of November and doesn’t depart until the first of July. The black clouds overhead mirrored those inside my head. I was suffering from a mental disorder known as clinical depression.

Slowly, I reached for the pen and began to write.

To my friends and family,November 12, 1996

I know that this is wrong, but I can no longer endure the pain of living with this mental illness. Further hospitalizations will not help, as my condition is too deep-seated and advanced to uproot. On some deeper level, I know that my work on the planet is finished, and that it is time to move on.

Douglas

I reached over for the bottle of pills that I had secretly saved for this occasion, slowly twisted off the cap and imagined the sweet slumber that awaited me. My reverie was interrupted by a loud knock at the door.

“Who can that be?” I wondered. “Can’t a man commit suicide in peace?”

I turned over in bed and spied my friend Stuart entering the living room.

“Just thought I’d check in and see if you made it off to day treatment,” he said cheerfully as he made his way to the bedroom.

I quickly hid the pills, wondering if I should tell Stuart about my note. Meanwhile, I could feel the stirrings of another anxiety attack. It began with the involuntary twitching of my legs, then violent shaking, until my whole body went into convulsions. Not able to contain the huge amount of energy that was surging through me, I jumped out of bed and began to pace. Back and forth, back and forth I stumbled across the living room, hitting myself in the head and screaming, “Electric shock for Douglas Bloch. Electric shock for Douglas Bloch.”

I had not always been so disturbed. Just ten weeks earlier, on September 4, 1996, I had taken a new Prozac-related medication in the hopes of alleviating a two-year, chronic, low-grade depression which was brought on by a painful divorce and a bad case of writer’s block. Instead of mellowing me out, however, the drug produced an adverse reaction—a state of intense agitation that catapulted me into the psychiatric ward of a local hospital.

Although it took only 24 hours for the adverse drug reaction to totally disable me, the roots of my depression extended far into the past. Although I have never formally investigated my genealogy, I know that the illness has run rampant in my family for at least three generations. Five of my family members have suffered from chronic depression; one developed an eating disorder and another a gambling addiction. One uncle died of starvation in the midst of a depressive episode. My mother suffered two major depressive episodes in a three-year period before she was saved at the eleventh hour by electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). I strongly suspect that both of my grandmothers lived with untreated depression all of their lives.*

Although one may be genetically and temperamentally predisposed to depression, it normally takes a stressor (personal loss, illness, financial setback, etc.) to activate the illness. A person with a low susceptibility to depression can endure a fair amount of mental or emotional stress and not become ill. A person with a high degree of vulnerability, however, has only a thin cushion of protection. The slightest insult to the system can initiate a depressive episode.

Two such insults had occurred in my life at the ages of twenty-six and thirty-three when the loss of love relationships plummeted me into deep depressions. The first breakdown resulted in a four-month stay in a halfway house in Berkeley, California; the second led to a one month residence in a New York psychiatric hospital. Fortunately, I was able to emerge from these ordeals fully intact (I later described the journey from trauma to recovery as breakup, breakdown, breakthrough). In 1984 I moved to Portland, Oregon, bought a house, married, found a great therapist, and began my present career as a writer. I was sure that I had left the dark house forever.

In 1993, however, a marital separation once again initiated a slow crumbling of my psyche, which culminated in February of 1996 when the divorce became final. I found myself too depressed to write and two months later learned that my publisher had let two of my most beloved books go out of print. My mental decline was further exacerbated by recurrent bouts of cellulitis—a strep infection of the soft tissue in my lower right leg—for which I was hospitalized and given massive doses of antibiotics. (Streptococcal bacteria have since been linked to anxiety attacks and obsessive-compulsive disorders.) Shortly afterwards, I developed chronic insomnia, a malady that had preceded my previous depressive episodes.

By summer’s end, I was, in the words of a friend, “barely limping along.” Although previous trials of antidepressants had been unsuccessful, on the advice of a psychiatrist, I decided to try a new Prozac-related medication, which had recently been approved by the FDA. Instead of calming me down, however, the drug catapulted me into an “agitated depression”—a state of acute anxiety alternating with dark moods of hopelessness and despair.

It soon became clear that taking this antidepressant had created a permanent shift in my body/mind. Before ingesting the drug, I felt crummy, but not crazy; emotionally down, but still able to function. My suffering was intense—but not enough to disable me, not enough to make me suicidal. Now, I had entered a whole new realm of torment. The drug’s assault on my brain caused something inside me to snap, sending me into an emotional freefall and creating a life-threatening biochemical disorder. The closest analogy I can use to describe my state is that I was on a bad LSD trip—except that I didn’t “come down” after the customary eight hours. In fact, the nightmare was just beginning.

There were two things about my predicament that made it different from anything I had ever experienced—the sheer intensity of the pain and its seeming nonstop assault on my nervous system. During my hospitalization, I discovered that my official diagnosis was “major depression” combined with a “generalized anxiety disorder.” Here is what I learned when I asked my doctor about these terms.

Major Depression

“If there is hell on earth, it is to be found in the heart

of a melancholy man.”

Robert Burton, seventeenth-century English scholar

Before I describe my own experience of major depression (also known as clinical depression), I would like to delineate the difference between the medical term “clinical depression” and the word “depression” as it is used by most people. Folks say they are depressed when they experience some disappointment or personal setback—e.g., the stock market drops, they fail to get a raise, or there’s trouble at home with the kids. While I would never want to minimize anyone’s pain, clinical depression takes this kind of suffering to a whole new level, making these hurts look like a mild sunburn.

Major depression can be distinguished from “the blues” of everyday life in that a depressive illness is a “whole body” disorder, involving one’s physiology, biochemistry, mood, thoughts, and behavior. It affects the way you eat and sleep, the way you think and feel about yourself, others and the world. Clinical depression is not a passing blue mood or a sign of personal weakness. Subtle changes inside the brain’s chemistry create a terrible malaise in the body-mind-spirit that can affect every dimension of one’s being.

“Melancholy” by Edvard Munch

For the benefit of the reader, I have listed on the next page the official symptoms of major depression, taken from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), the official diagnostic resource of the mental health profession.

While the clinical criteria depict how a clinician views major depression, describing how depression actually feels—especially to someone who has never “been there”—is not so straightforward. If I told you that I had been held hostage, put in solitary confinement and beaten, you might receive a graphic image of my suffering. But how does one describe a “black hole of the soul” where the tormentors are invisible?

I remember a diagram from my high school biology class depicting what happens when you put your hand on a hot stove. The nerve receptors in the skin send a message up the arm and spinal column to the brain, which interprets the situation as “Ouch, that’s...

All prices incl. VAT